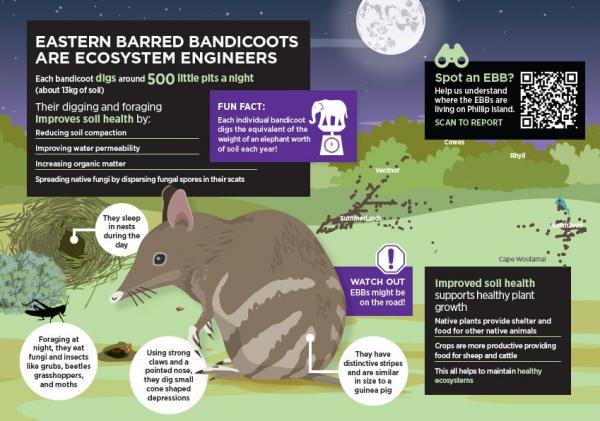

All about the Eastern barred bandicoot

The Eastern barred bandicoot is one of Australia’s most fascinating native animals. These small nocturnal marsupials were once widespread across southwest Victoria and Tasmania.

Today, the mainland Eastern barred bandicoot is endangered due to predation by foxes and the loss of much of its native habitat.

Fortunately, thanks to efforts to reintroduce the Eastern barred bandicoot into the wild on offshore islands, including Phillip Island and Churchill Islands, this species has been brought back from the brink of extinction.

Why do we need to save the bandicoot?

Eastern barred bandicoots are unique to Victoria and one of our rarest animals. Its near extinction as a result of predation by foxes and the loss of 99% of its native grassland habitat.

Where do Eastern barred bandicoots live and eat?

The Eastern barred bandicoot is a small brown-grey marsupial with distinctive pale bars or stripes across its back, pointed ears and hind legs that look similar to a kangaroo.

Grasslands and grassy woodlands provide the complex habitat preferred by these shy animals. They use their clawed forepaws to scrape out a depression which they line with grass. These nests tucked under tussocks of grass protect the bandicoots during the day while they sleep. While they are solitary creatures, mother bandicoots will share their nests with their young.

When it comes to diet, Eastern barred bandicoots are omnivorous, which means they eat a variety of plant and animal matter. However, they mostly feed on the grubs of beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, moths and earthworms. They use their strong claws and pointed nose to dig for food, leaving small cone-shaped depressions. They have also been found to eat a small amount of onion-grass bulbs and fallen fruit. They forage at night, leaving their nests within two hours after sunset.

Will they eat native orchid bulbs?

Eastern barred bandicoots are primarily insectivorous and only eat small amounts of plants, such as bulbs of onion grass and fallen orchard fruit. Studies of their diet at several release sites have not found any indication that they eat native orchids, despite the native grasslands where they live being rich in orchids, indicating that the two can coexist.

Download Eastern barred bandicoot infographic here.

The bandicoot circle of life

Eastern barred bandicoots have a very rapid breeding cycle. Babies are born 12.5 days after breeding, with 1-3 babies in each litter. The babies stay in their mother’s pouch for 55 days before they wean, and leave the pouch at about three months of age. Females can produce up to five litters a year, however breeding happens less frequently in summer and during times of drought.

Bandicoot conservation efforts

By 1972, bandicoots were down to one wild population in Hamilton, Victoria. From this population, 42 animals were taken into captivity in 1988 to form a breeding program to conserve the species. From these 42 animals, just 19 successfully contributed to the breeding program.

In initial efforts to return the Eastern barred bandicoot to the wild, eight reintroduction sites were established. In 1989, the first ten bandicoots were trial released into Woodlands Historic Park. From here further populations were introduced to Hamilton Community Parklands (1989), Mooramong (1992), Floating Island Nature Reserve (1994), Lake Goldsmith Wildlife Reserve (1994), Lanark (1994), Cobrac Killuc Wildlife Reserve (1997) and Mount Rothwell (2004). Of these eight sites, three are home to breeding bandicoots today, with others failing primarily due to predation by foxes.

Island Introductions

In recent years fox-free islands have provided a refuge for Eastern barred bandicoots. Introductions were made onto Churchill Island in 2015, Phillip Island in 2017 and French Island in 2019, providing 70 square miles of bandicoot habitat. The bandicoots have been breeding and spreading across these islands, and Churchill Island has provided an excellent source population for introductions into other areas.

In September 2021, thirty-three years after Eastern barred bandicoots were first taken into captivity, their numbers had increased to around 1500 individuals and their status was changed from Extinct in the wild to Endangered. In a world first this has allowed the captive breeding program to come to an end. Ongoing research has shown that their numbers and range are increasing, a promising sign for the future of this incredible marsupial.

Check out the story map here.

Why release on Phillip Island?

The release of endangered species into the Nature Parks has been identified as a desired action in major planning documents that were developed in consultation with staff, major stakeholders and the community. These include the Phillip Island Nature Parks Strategic Plan 2012-2017 and Environment Plan 2012-2017. An external review conducted by the IUCN Conservation Breeding Specialist Group found that releasing the Eastern barred bandicoot onto a large fox-free island is the only course of action that may result in reasonable prospects for the long-term survival of the species.

What did the Churchill Island trial show?

Churchill Island was used to evaluate the suitability of the local conditions for the marsupial and to demonstrate to the community what they might expect from an Eastern barred bandicoot release. Bandicoots successfully established on Churchill Island growing from 20 animals to about 120 in two years. The population has stopped growing and has stabilised at around this number.

There have been no negative effects on the island's habitats caused by Eastern barred bandicoots. In fact, there have been positive effects recorded; diggings have reduced soil compaction, and we have seen improved nutrient and water infiltration.

Will they become a pest?

Eastern barred bandicoot monitoring at release sites over the last 28 years has revealed seasonal fluctuations in population size and number of young born. This is most likely due to fluctuations in resource availability. Densities are typically one to two bandicoots per hectare and there have been no reports where the species has been considered to be overabundant. On neighbouring Churchill Island densities have levelled off at around two Eastern barred bandicoots per hectare.

Will they cause any damage to the island?

Eastern barred bandicoots do not graze or browse and leave very little sign of their presence besides small conical foraging digs that are rarely more than 5 cm deep. There have been no reports of this marsupial negatively impacting natural habitats and it is important to remember that this vulnerable species needs assistance as it is currently Endangered.

How can I see an Eastern barred bandicoot?

Bandicoots are very inconspicuous animals and are easily overlooked. This is because they only come out at night and do not form groups. Your best chance of spotting one is by torch in cleared areas at night, when they are most active.

More quick bandicoot facts

-

Weight: 600 - 800g

-

Length: ~400mm

-

Life: 2-3 years

-

Kingdom: Animalia

-

Phylum: Chordata

-

Class: Mammalia

-

Order: Peramelemorphia

-

Family: Peramelidae

-

Genus: Perameles

-

Species: Perameles gunnii

Download our print-friendly bandicoot guide here.

Download bandicoot friendly garden brochure here.

Find out more about our conversation efforts for the Eastern barred bandicoot here.